Solar energy powers up sister-city partnership

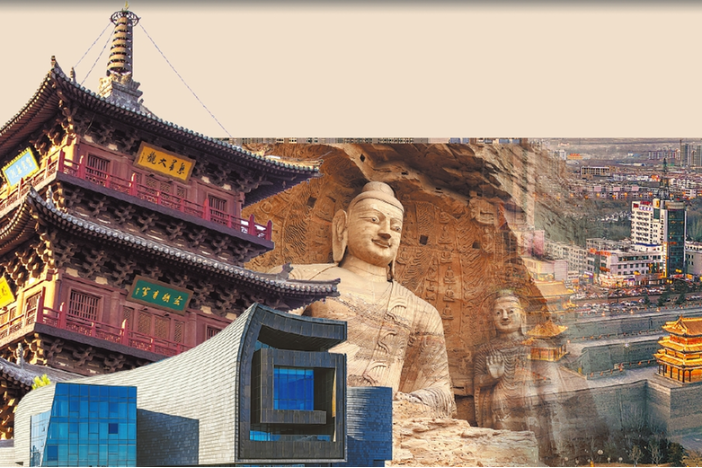

In the 1980s Chang Weiming's hometown of Datong in North China's Shanxi province was commonly nicknamed the city of coal as it fueled China's industrialization with its resources.

In fact since New China was founded in 1949, Shanxi has delivered more than 3 billion tons of premium thermal coal, keeping hundreds of millions of people warm and stoking industrial and economic growth.

However, the warm glow that this delivered had a darker, more somber side. As a child, Chang lived next to a thermal power plant and recalls his school years under leaden skies shrouded in coal dust.

"In those days no one dared wear white shirts outside because with a few gusts of wind your clothes could be ruined instantly," said Chang, 39, now a power project engineer.

However, those days are long gone, Datong having given itself a far-reaching environmental makeover. Cutting-edge, intelligent mining technologies and renewable energy infrastructure have converted this traditional coal base into a green energy hub, and it was one of China's national new energy demonstration cities.

"Modern Datong embodies smart mining, solar farms, wind turbines and azure skies," Chang said.

"While Cambodia lacks substantial coal reserves, its green energy imperatives align closely with Datong's transformation. Both regions share solar energy advantages."

In 2020 Chang was project manager at a 30-megawatt solar power plant in the northwestern Cambodian province of Banteay Meanchey.

Shanxi Electric Power Engineering Co, a subsidiary of the China Energy Engineering Corporation, was in charge of the engineering, procurement and construction of the project.

The solar plant was the first fully grid-connected project among Cambodia's initial five photovoltaic demonstration initiatives and the largest renewable energy installation in the province.

Five years later, in February, the company secured another big engineering, procurement and construction contract in Cambodia, for a 250 MW solar farm in the southern province of Prey Veng. The installation, covering 253 hectares, is due to be commissioned next March.

Transition needs

These renewable energy projects strongly align with Cambodia's energy transition needs, experts said.

In 2022, the country's energy mix was well out of kilter, the Electricity Authority of Cambodia said, with hydropower accounting for 53.9 percent, coal and oil 38.9 percent and solar a mere 6.7 percent.

This heavy reliance on hydropower makes the energy system highly vulnerable, particularly as climate change disrupts rainfall patterns, and both droughts and extreme rainfall events destabilize hydroelectric output.

During the historic dry spell of 2022, plunging hydropower generation forced Cambodia to import fossil fuels, with more than a quarter of its electricity imported from Thailand, Laos and Vietnam.

Consequently, Cambodia has some of the highest electricity costs in Southeast Asia, according to the website Energy Tracker Asia.

In its Power Development Master Plan 2022-40, Cambodia has said that by 2030 it aims to have hydropower account for 27.7 percent of domestic energy and solar power 17.9 percent of domestic energy.

By 2040 it hopes that hydropower will account for 21.4 percent of that energy use and solar power 29.8 percent.

The newspaper the Khmer Times quoted Akshay Pattumuri Venugopal, a renewable energy expert and technical consultant based in Phnom Penh, as saying that Cambodia possesses the potential to emerge as a solar energy champion.

"Cambodia enjoys ample sunshine throughout the year, making it an ideal location for solar energy."

The environmental advocate Eric Koons said in an analysis that solar energy in Cambodia is cheaper to produce than most other alternatives, yet the solar energy market is largely untapped.

In fact, the team that worked on the Banteay Meanchey project said it encountered unprecedented obstacles during initial construction.

In October 2020 successive typhoons triggered Cambodia's worst flooding in 50 years, claiming more than 40 lives and displacing hundreds of thousands of people. Floodwaters inundated the site for more than a month, in some areas reaching depths of 2 meters.

"Not an ounce of experience in Datong prepared us for this catastrophe," Chang said. "In fact, the complete submersion initially overwhelmed us."

Improvisation proved crucial: technicians built pontoon rafts from fuel barrels to transport components, and workers waded through waist-high water to carry out construction work.

Despite widespread construction halts elsewhere, the team achieved on-schedule grid connection.

The plant now generates 160,000 kilowatt-hours of power a day, providing electricity to at least 80,000 households based on World Bank figures showing Cambodia's average monthly household consumption at 55.2 kWh.

Enduring bonds

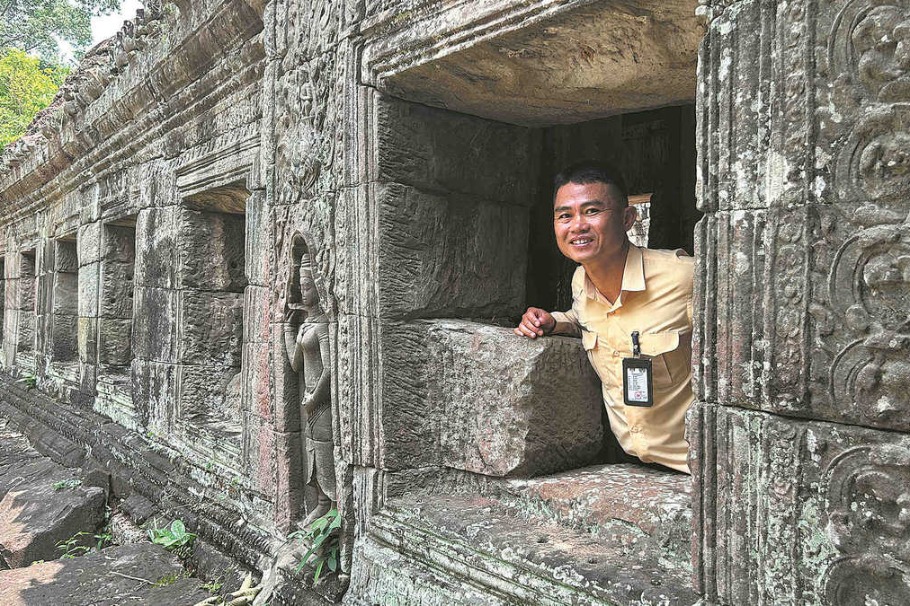

Chuoy Rath, 35, a Cambodian working on both projects in Banteay Meanchey, said the benefits were clear.

"Since operations began, power outages have vanished. Local businesses operate uninterrupted, and households are paying less for their electricity."

Chang underlines the importance of sharing knowledge.

"Pairing Chinese technicians with Cambodian workers created jobs, building local technical capacity for long-term maintenance."

Work on the 250 MW project in Prey Veng is now in full swing, and two countries — one that gave light to China and one that seeks light through solar — are writing new energy stories together.

Once the Prey Veng plant comes onstream it will significantly advance the country's goal of exceeding 1 gigawatt of photovoltaic capacity by 2030, according to the Cambodian Ministry of Mines and Energy.

Wang Xinping, head of the Shanxi Electric Power Engineering Co, said: "The new project will strongly support Cambodia's green transition, accelerate renewable energy adoption and drive structural transformation of the energy sector."

As technical achievements were being chalked up, human connections deepened. During floods, the team delivered emergency aid, including 8 tons of rice, 200 cartons of noodles and 400 water boxes, to 160 households, as well as educational materials to the Preah Netr Preah Primary School.

Chang frequently traveled 100 kilometers to Siem Reap with Cambodian colleagues for supplies. Visiting Angkor Wat, he reflected, "As I have worked there, the sister-city ties have given me a profound sense of connection."

Chuoy said: "Collaborating with Shanxi colleagues feels like brotherhood; it is an unbreakable bond."